[Klik hier voor de Nederlandse versie van deze post]

Organizations are an inseparable part of our social life. Yet they are strange, as they do not fit into the moral system that has been developed since the Enlightenment. In that system, the market and state operate as accountability structures, establishing a relation between individual persons and institutional domains, making it possible to hold individuals responsible for their functioning. With the emergence of organizations, the workings of accountability structures seem to have lost their strength, because from the point of view of social domains such as the market and the state, organizations function as individuals, while individuals in turn obey the rules of the organization. That leads to all kinds of moral and social problems that are not well recognized because organizations are often seen as actors, just like people − something they can never be.

—

Look inside a book on economic theory and you will learn that you can see a company as a single entity that makes strategic choices. Just like an individual.

Few claims seem as easily falsifiable as these, after all, companies can have thousands of people working for them who all do their own thing. Yet many economists are stubbornly holding on to the idea of the company as an individual.

In the neoliberal dogma, companies and individuals even occupy a similar moral position. According to that dogma, both strive for the same thing: optimization of their own utility function and if we give companies and individuals the same rights, the aggregation of decisions based on self-interest will yield an optimum level of prosperity. According to this thinking, it would therefore be best to limit companies as little as possible, just as we also allow freedom for autonomous persons.

—

Advocates of the neoliberal dogma are keen to refer to Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations from 1776. After all, in this book, the idea was systematically elaborated that the aggregation of individuals who acted on the basis of self-interest could lead to the greatest possible social wealth.

Smith also presented in this book the example of the pin factory, advocating the benefits of division of labor. If workers focus on one specific task and there are enough workers who have tasks and there is sufficient demand for pins, then there will be a huge increase in production.

But Adam Smith’s pin factory is in little comparable to the Fortune Global 500 companies. The pin factory’s boss was actually the boss: he was the owner and manager in one. But those functions also fell victim to division of labor. Nowadays, owning an organization is sometimes in the hands of thousands of shareholders, who are organizations themselves, such as pension funds or investment companies. The management of a large company has a hierarchical, command and control structure, which can also result in thousands of fte’s in management functions.

The boss of a company like a needle pin coincides, as it were, with his company. If the company is not doing well, then the boss was also the victim. You could not even appoint the owner of a multinational, even at a shareholders’ meeting there is only a selection of them in a large room. If things go wrong with the company, the shareholders lose some money, which they probably have spread over many different companies. Shareholders can also pursue a different managerial course, perhaps by installing a different CEO − the person most identifiable with such a company as a whole, but ultimately also a passer-by with a well-paid contract. In the end, a company coincides with nobody in particular.

—

This difference also leads to a difference in moral responsibility. An organization is not a person. This certainly does not only apply to market organizations, but also to government organizations. Here too, there may be a minister or alderman who is functionally responsible for the ins and outs of such an organization, but it is difficult for this person to be morally responsible for everything that is going on within such an organization.

Since the Enlightenment, an institutional structure has been developed based on the possibility of holding individual actors accountable for their decisions. Most typical this is the role of the court. If you do something wrong by breaking the law, you have to account for this action before a judge or jury. After that, you can, for example, get fined or go to jail.

One finds the same idea in parliamentary democracy. A minister who does something wrong can be dismissed by the parliamentarian. If a parliamentarian does not do well, she will be ‘punished’ at the next election and lose her seat.

The market is also such an accountability structure. The producer of things that nobody wants or is way too expensive is not doing well and will be ‘punished’ by the absence of customers. In the end, it can even go bankrupt.

What we see here is that within a social domain such as the state or the market, individuals can be held accountable for their decisions. If these individuals make mistakes, they can be penalized for that afterwards.

The presence of accountability structures ensures that individuals are better able to do their best, since they take into account the possibility of punishment afterwards. In this way they learn to take responsibility for the decisions they are going to take in advance.

—

The relationship between a social domain and an individual changes structurally with the arrival of organizations. As an employee in a large company or as a civil servant in a ministry, you cannot be directly addressed by a client or parliamentarian. You mainly listen to your supervisor, who in turn also listens to a supervisor. What society as a whole demands from you is quite unclear.

With this, organizations have in fact taken the place of individuals. But organizations respond in a completely different way to individuals. Organizations have no pain, no pleasure, they don’t die.

As I have written before, a moral awareness requires a recognizable body, an undivided memory, and a single consciousness. The body of an organization is amorphous, the memory of an organization is distributed over databases, in forms and in the memories of countless employees and it would be silly to speak of the consciousness of an organization.

If you already assign a life cycle to organizations (and there are countless examples of this in the literature), then it is about lives with a sense of time and space that is completely incomparable with that of people.

This implies that the moral responsibility that was formed in individuals by the presence of liability structures is only present in a very diluted way.

—

Historically, this state of affairs can be explained. The design of domains such as the state and the market was roughly devised in the eighteenth century. I have already mentioned Adam Smith as the founding father of market-based liberalism. It was not without reason that Smith was a moral philosopher, but you can also think here of Montesquieu whose De l’esprit des lois dates from 1749. The modern organization comes from at least a century later.

Alfred Chandler describes how that modern organization came about. He states that we must look at the development of the railways in the United States in the nineteenth century. The construction and management of those railways could not be done by a single boss who controlled all employees from his office, they were far too far away for that. The company had to be designed as a multi-unit enterprise, the various units of which were managed as separate units by hired managers.

Chandler called his book The Visible Hand, as an explicit counterpart to Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ that ensured that the market functioned properly. With the manager’s visible hand and the emergence of the modern organization, the invisible hand that takes care of the discipline of the market becomes a lot less strict.

—

The railway company has become the model of every modern organization − both public and private. Helped by insights such as, for example, the ones presented by Frederick Taylor in 1911 in his book The Principles of Scientific Management. He showed that employees proved to be perfectly capable of being used as parts of a large machine. Something that was also observed by Thorstein Veblen and Max Weber, albeit a lot more critical.

Not only blue collar workers, but also the clerks and the managers came to identify themselves with the organization they were part of. Where the rhythm of the workers was determined by the speed of the assembly line or other mechanized processes, the clerks and managers are mainly concerned with their motivations and orientations. The decisions they make are decisions that they think are going to the benefit or interest of the organization as a whole. It appears that they surrender a substantial part of their individual moral abilities in favor of an amoral phenomenon.

As said, organizations do not know intrinsic morality, that is a characteristic reserved for people only. If you then assign organizations the responsibilities of individuals to individuals, something goes wrong. That is quickly reminiscent of a Marxist ‘Verelendungstheorie’, but that is not exactly what I am aiming for. It is not alienation, but it is just weird that non-moral entities have taken the position of moral beings.

—

Back to the neo-liberalism that I started this piece with. The legitimacy of this ideology is above all based on an aversion to organizations that belong to the domain of the state. This domain lacks the ‘incentives’ of the market that make a company flexible and innovative, as opposed to the sluggishness of government agencies.

But the discipline of the market only applies to a limited extent to large companies, which thus gain a huge advantage over smaller companies. These may be more flexible and innovative, but they also go bankrupt much faster. This makes neo-liberalism an ideology that is intrinsically unjust, not only with regard to smaller companies, but even more so with regard to the protection of the rights of their employees.

Moreover, neo-liberalism is based on a wrong assumption. After all, organizations are not intrinsically public and private. As stated above, they take over the position of individuals with regard to the domain of the state or the market, or they take over the position of those domains from the perspective of the individual employees.

The larger organizations become, the less they have to give consideration to pressures imposed by their institutional environment and the more they become alike. Joseph Schumpeter argued that capitalism and socialism would increasingly come to resemble each other, in the end, bureaucracies would dominate both the market and the state.

—

It is therefore a mistake to think in terms of market and state or market versus state. We need a fundamental mistrust of every large organization, because they reduce our moral abilities.

Currently, the largest organizations are multinationals, barely tied to specific locations, they can freely evade regulation or have the laws changed to their advantage. A counterforce is more than necessary here. Large state organizations seem to be the most obvious counterforce. But they also have to be distrusted just as much.

The question is not how we can make the organization responsible, we must be content with making them more responsive − to the extent that this is possible. The question is how an organization, with all its ingrained bureaucratic tendencies, can change if society finds it necessary. For example, how can we ensure that business activities do not just come at the expense of the environment or the well-being of people or how ministries choose not for the importance of the rules but for the interest of the citizens? I think that this is only possible if we become fully aware of the simple fact that organizations are not people, and that we do not equate them like we are accustomed to do in law (think of ‘legal persons’), in economic theories (see above) or in social sciences (think of ‘stakeholders’ and ‘actors’) − because then it will be humans who lose.

—

Further reading:

Chandler, A. D. (1977). The visible hand: The managerial revolution in American business: Harvard University Press.

Dewey, J. (1922). Human nature and conduct: Courier Corporation.

Friedman, M. (2009). Capitalism and freedom: University of Chicago press.

Merton, R. K. (1940). Bureaucratic structure and personality. Social forces, 18(4), 560-568.

Montesquieu. (2002). The Spirit of the Laws. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pesch, U. (2005). The Predicaments of Publicness. An Inquiry into the Conceptual Ambiguity of Public Administration. Delft: Eburon.

Schumpeter, J. A. (2000). Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. London and New York: Routledge.

Smith, A. (1998). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. A Selected Edition. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, F. W. (1914). The principles of scientific management: Harper.

Van Gunsteren, H. (1994). Culturen van besturen. Amsterdam & Meppel: Boom.

Veblen, T. (2005). The theory of the leisure class; an economic study of institutions: Aakar Books.

Weber, M. (1972). Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Grundriss der verstehenden Soziologie. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr.

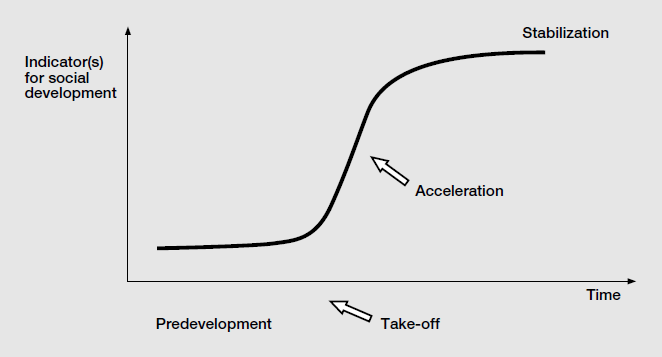

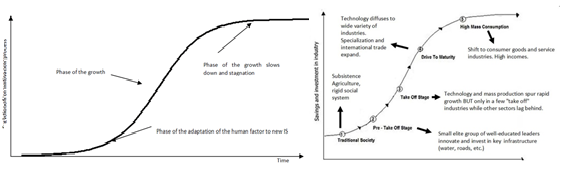

With his curve, Rogers described the way in which the market adopts a new innovation. First there are few users, only a small group of early adopters. If the technology catches on, then more and more people will start using the product and an acceleration will take place until the market or society becomes saturated and the growth of development flattens out.

With his curve, Rogers described the way in which the market adopts a new innovation. First there are few users, only a small group of early adopters. If the technology catches on, then more and more people will start using the product and an acceleration will take place until the market or society becomes saturated and the growth of development flattens out.